Prof. Ashok Sahni (b. 1941) is one of India’s best known palaeontologists. He was part of the Indo-US team of researchers who discovered and reconstructed Rajasaurus narmadensis, a 9-meter long carnivorous dinosaur whose remains were found in the Narmada region in India. Prof. Sahni received his MSc in Geology (1963) from the University of Lucknow and his PhD in Geology (1968) from the University of Minnesota. He is currently Emeritus Professor at Panjab University, Chandigarh. In 2011, he received the National Geoscience Award for lifetime achievement and professional excellence, including in the field of science popularization.

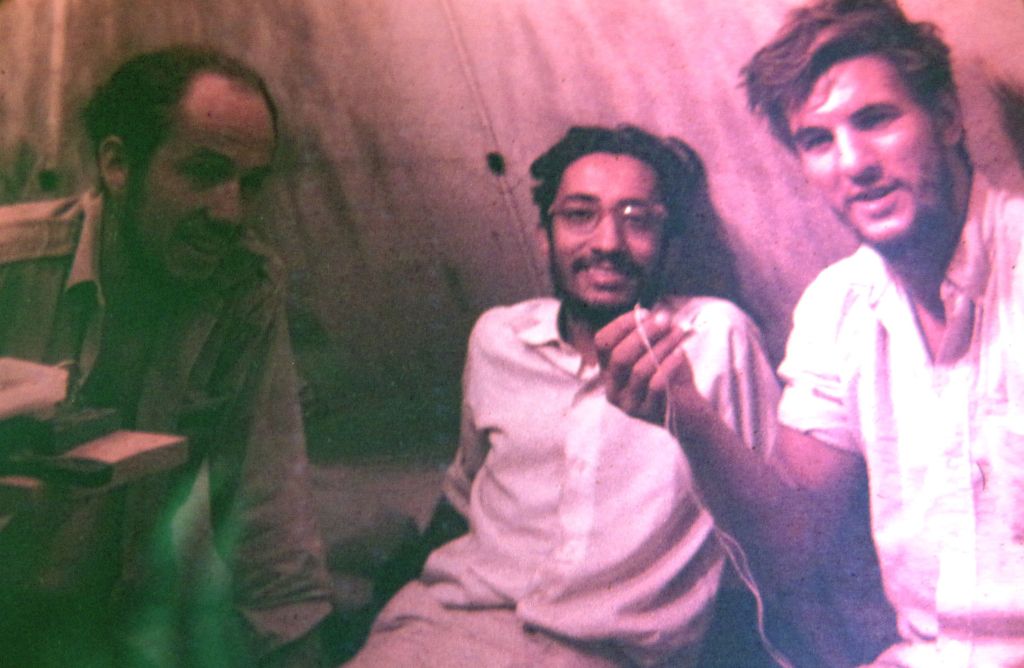

*****

AB: Prof. Sahni, I would like to begin by thanking you for agreeing to inaugurate this archive of conversations about science. As I have mentioned before, the project I am currently working on—a history of Earth sciences and historical imaginaries in twentieth-century India—grew out of a footnote in my first book, a footnote about your grandfather, Ruchi Ram Sahni. I did not know you at the time nor did I know where that footnote would take me. But as I try to turn it into a book and use the project as an opportunity to reflect more broadly on the myriad ways in which science permeates our lives, I am grateful that you have so generously agreed to embark on this journey. So let me begin by asking you, how did you become interested in science?

AS: To put this question in a personal context, my parents were rather special with regard to their educational backgrounds. They got married in 1931. My father had been educated at the University of Cambridge, the British Museum and had also completed a D.Sc. in Geology (Palaeontology) from the University of London. My mother, on the other hand, had a Master’s degree in Political Science from the University of Lucknow, a rare occurrence for women in India in the late 1920s. Given this rather unique state of affairs, it was no surprise that their children would be inquisitive and argumentative about everything that was being discussed in the house. Add to this the fact that our home was a temporary storehouse for some specimens my father brought from his frequent field trips as an officer of the Geological Survey of India. He would talk about incidents during fieldwork and the meaning of the fossils collected. He had a knack for anecdotal narrative which always ignited my desire to follow him!

We were very liberal in our views. As a family, we were not at all religious. My father was a Darwinian in soul and spirit. He must have got this from his father—my grandfather Ruchi Ram Sahni—who twice changed his religious beliefs before the age of 20, much to the consternation of his mother, my great-grandmother! Certainly, it was a family of liberal thought. I grew up in this environment and was gradually drawn to science, a science that required field materials and interpretation, not the science of the precise such as physics or mathematics. In fact, after so many years of research in palaeontology, I still like the fact that there is nothing absolute in the inferences drawn. The truth keeps changing and keeps reminding me how little we know.

AB: I know that engaging with a wider audience than that of professional scientists has been an important aspect of your work. How would you describe your job to someone who is not familiar with palaeontology?

AS: I have always been puzzled by the fact that people look at the same issues and objects differently, so very differently. What is obvious to me is not obvious to them and vice versa. Why is that so? I tried very hard to see scientific problems from others’ point of view. In arguments with my colleagues and students, I always played the role of the devil’s advocate, to find out what the other side of the coin looked like. I learned a lot from this exercise. It made me more liberal in my views. A medieval Indian sage, Kabir, once said that ‘in life, always keep a critic by your side.’ I have tried to follow this dictum!

I love teaching, especially to young school children. Palaeontology appears to be particularly captivating for young minds and asks so many basic questions: How did life originate? Why are we the way we are? What will happen in the future? I have been involved in several programmes dealing with the popularization of science, for example as part of the Indian National Science Academy School Seminar, held in 1994 in Chandigarh.

Research, on the other hand, led to several new findings in India and this kept me and my students involved for a long time. One aspect of this research dealt with Indian dinosaurs, a subject which had become popular in India after the film Jurassic Park was dubbed in Hindi and became a topic of general discussion. In 1994, when a local carnival was taking place, we asked for floor space in the Natural History Museum in Chandigarh. My students and I were amazed to see the flood of people who visited and how much they knew about past life, an aspect I had never considered before. It was an eye opener and I was finally able to establish a permanent exhibition in the same museum in 2005.

AB: As a historian, I spend a good part of my working time indoors (usually sitting!). By contrast, you have set office, so to speak, on much more challenging terrain—places that most of us can only dream of visiting. Could you tell us more about the sites where you conducted fieldwork and how you reconciled those excursions with work in the laboratory and teaching?

AS: One of the joys of palaeontology is discovery; the other is seeing new, strange places, where most people may never set foot in their lifetime. The first time I went on fieldwork was for my doctoral dissertation, in a desolate region of Montana. I was about 22 years old. It remains to this day one of the most memorable experiences of my life. I loved fieldwork: from Kashmir and Ladakh to the coastal regions of south India, from Gujarat in the west to Mizoram in the east, I went hopping from one site to another!

The interpretation of fossils collected in the field requires very good infrastructure facilities. As university departments at that time were not well equipped, we ended up building our own small labs for processing field material. We even built a dark room in a corner of my office to develop our own photographs.

AB: Fieldwork can sometimes be an intrusion or even a threat. How have local communities responded to or been involved in your research activities?

AS: All over the world, a geologist working in the field meets resistance from the local community, whether it is in the United States or in India. The laws for collection and ownership are different. In the US, you must be careful who owns the land where you collect fossils. In my case it was a rancher with extensive lands who really did not care much. I ended up naming a species after his ranch! [AB: The primitive Cretaceous marsupial Alphadon halleyi, named after the Halley Ranch on the Missouri River, near Winifred, Montana.]

In India, conditions are different. In the 1960s, the local community was very welcoming, but things have changed now. All wish to know whether money is to be made!

AB: To return to teaching, what do you think makes a good teacher of science? Conversely, what are some of the most important lessons you have learned from your students?

AS: Teaching is a balancing act. The main hurdle lies in making your material understandable to everyone in class and making it interesting at the same time. During lectures, I used to ask students questions all the time about the subject I was teaching and I suppose this kept them awake! I also made use of graphics, photographs and, of course, specimens. One problem is that in India the ‘distance’ between a teacher and student (the guru-shishya parampara, teacher-student tradition) is sacrosanct. I tried to do away away with this. I also learnt that if I made a mistake while teaching a particular point, I should openly acknowledge this and correct it.

AB: If you were to pick one achievement that you are particularly proud of, what would that be?

AS: This is an easy one—seeing the enthusiasm and output of my academic children and grandchildren, that is, my students’ students!

AB: The myth of the solitary genius has been quite pervasive in popular culture, but as historians of science have also shown, scientists rarely work on their own. How important has teamwork been in your own career? I am referring here both to collaborations within your own institution and those that transcended local and national boundaries?

AS: Once, when I was giving an invited lecture at an institute, I started by saying that I was standing before them that day because an army of students was standing behind me. I know this from personal experience. I always felt that science is teamwork and that ideas can come from anyone; the more experienced you get, the better your ideas might become, but in the end it is only teamwork that counts. In fact, when I started research in India, I had three PhD students. I made it a point to send all three of them to each of the localities that would have been covered by a single student because more eyes meant more material, more bonding, better teamwork. It paid off and many sites of fossils still important today were found in this manner. These three initial students are still friends 50 years later!

I have been lucky with all my foreign collaborations. Scientific collaborations are like a marriage where the spirit of give and take must reign supreme and ego has to take a back seat! Stable collaborations are those when equal respect for each other prevails. The biggest dissensions come during publication time and usually with regard to the order of authorship, especially if the discovery is of great importance. Some scientists are so particular about this that the whole project can end up being jeopardized. My personal collaborations, of which I have fond memories, include those with the Universities of Montpellier and Paris VI, The Steinmann Institute of Palaeontology, Bonn, Johns Hopkins University and the Royal Institute of Natural History in Brussels. Apart from this I have had the pleasure of working with many individual foreign scientists from whom I have learnt a lot.

AB: One of the aims of my current project is to write an inclusive history of science that draws attention to the many actors—such as lab technicians—whose contributions to the making and communication of scientific knowledge are usually overlooked. Who, in your opinion, are the unsung ‘heroes’ of science?

AS: You are correct. Look at this from the perspective of a young Indian student working in the US. Professors are so busy that it is very difficult for them to spare time to answer your never ending questions. Who do you turn to? In my case, the technical help at the University of Minnesota was of great assistance, providing advice on sitting space, microscopes and how to go about my work. He was always there and had a smile on his face, taking everything I said very seriously!

Undergraduate students who wanted to go to the field for the fun of it also deserve to be mentioned. I greatly benefited from the help of a student named Noel Waechter. He knew the norms of his society and talked to ranchers and farmers on whose lands my sites were located. I could never have managed on my own in that desolate part of Montana, where I was an oddity in 1965—a palaeontologist from India, the land of ‘snake charmers’! Most of my productive fieldwork was conducted with his help and we are still in touch today.

AB: The 2018 fire that destroyed the National Museum of Brazil as well as a similar incident at the National Museum of Natural History in Delhi in 2016 have highlighted some of the chronic problems that beset many natural history and anthropological museums around the world. When not facing downright closure, such institutions have been increasingly forced to rely on project and crowd-funding to make up for dwindling state support, including lack of investment in daily maintenance and basic infrastructure. In India itself, there have also been cries that disciplines like palaeontology might be on the brink of extinction—much like the dinosaurs it studies, if I am forgiven this comparison. Why is it important to continue studying palaeontology and Earth sciences more generally and how can we address the problems these disciplines are facing in India?

AS: For a country like ours, the central problem is whether to encourage basic or applied research, enrich and encourage the humanities or other similar subjects or build technology-based institutes where the returns are more obvious. Museums are usually not financially self-sustaining and may need continuous external resources to run. They fall more in the area of infrastructure development, where the gains may accrue only in the future and may not be quantifiable.

Palaeontology falls under the category of basic sciences. Its greatest charm is that it draws young children from all walks of life, challenging them to think about science and prehistory. For some of these children a visit to the museum can be a defining moment in their lives. I believe that this is what it is all about. I have tried for many years to convince authorities to build a Natural History Museum, but it has not happened so far. We are still trying and being hopeful.

AB: One final question, is science for everyone? What can we do to reach a broader audience and in particular those groups and communities who have been underrepresented, e.g. women and minorities?

AS: Science as a profession is not for everyone, but science certainly is. Personally, I have never paid attention to someone’s gender or minority background, what mattered was whether the student was willing to study, was capable and motivated. The two women who completed their PhDs with me—Dr. Kalpana Deka Kalita and Dr. Shashi Kad—are both doing well in their fields. Unfortunately, it is not common for women to complete PhDs in geology. This is a problem in many fields of science. In fact, in 2004, I was a team member in a project called ‘Science Career for Indian Women,’ which examined Indian women’s access and retention of science careers and produced a report on this matter. [AB: The report is available here.] There is certainly a lot of work to be done.